The Future of Education in the Age of AI: A key insight from Peter Vesterbacka, founder of Slush, emphasizes that education systems should shift their focus from competing with machines to developing skills that machines cannot replicate, such as critical thinking and creativity.

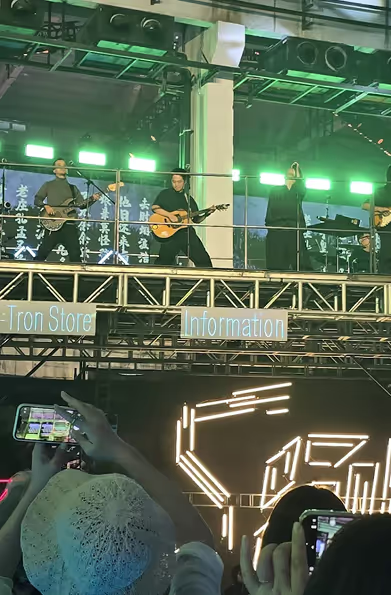

Let’s get this out of the way first. All tech conferences should feature rock bands at lunchtime. Shanghai’s S-Tron Startup fest bills itself as “the coooooooolest (sic) tech innovation and startup-focused event in Asia,” and having seen hundreds of startup founders and conference volunteers rocking out, I think they’re onto something. We’ll come back to branding later on but suffice to say, this was a great idea Sean Song.

Now, onto the substance. Like every other tech and startup event around the world, the focus of many—if not most—conversations was AI. What industry will it eat next? What applications actually have sustainable value?

The most compelling discussion, for me, was between S-Tron President Sean Song and Peter Vesterbacka, founder of the Slush series of tech events. Fifteen years ago, he launched Slush as an alternative to orthodox Silicon Valley cheerleading. Among Peter’s insights was a focus on how societies and their policy leaders can best prepare for the disruptions caused by AI.

He noted:

“The pace of technological advance means that you shouldn’t be training youth to compete with machines that will learn faster than we can ever hope to. Rather, we need to learn what machines cannot do and focus our education systems there.”

He added:

“Education systems that understand this nuance and can shift from traditional methods and content will win this race in the medium to long term, regardless of whether they show early-mover advantages.”

Vesterbacka pointed to the relative success of Nordic countries in the tech world, where—despite small populations—cities like Stockholm, Copenhagen, and Helsinki produce the most unicorns per capita outside of Silicon Valley. He attributes this success to education systems that accept authority is to be questioned, thereby fostering critical thinking and student engagement.

Discuss amongst yourselves whether your school board is ready for that. Ahem.

I was at S-Tron to join a conversation about emerging markets and what lessons might transfer from Asia’s evolving ecosystems to those developing in Africa today. I was joined on stage by three fantastic panelists with complementary perspectives: Oscar Ramos, an emerging market VC; Sebastien C., a Shanghai-based entrepreneur who has expanded his startup into several African markets; and Nathaniel Witbooi an ecosystem builder from Cape Town who has relocated to Shanghai to build China-Africa engagement.

If this potential is unleashed, the global innovation economy will see countless new competitors vying for scarce capital, customers, and ultimately—attention.

And here’s where branding comes to the fore. In a world where digital opportunity is increasingly evenly distributed, how ecosystems capture the attention needed to help their startups grow becomes key. What differentiates your ecosystem from others? What branding will resonate with a global class of corporate partners, investors, and talent looking for what’s next, unrestrained by borders?

As Vesterbacka noted—echoing what many others have said before him—specialization is critical. It’s not enough to be another ecosystem that’s “great at AI.” You need a differentiated brand that stands out among global competitors. Applying new tech to specific problems or sectors—like what I recently saw in Mongolia—is central to that branding. And it will only grow in importance as ecosystems across emerging markets step onto the global stage.